Did you spot us on Channel 5’s The Great Stink documentary?

The Grand Junction Waterworks Company (GJWW) played a major role in providing clean water to London’s ever-growing population. For those who were able to have piped water, their drinking water had been filtered and cleaned for about 30 years before the Great Stink happened.

What was the journey that the GJWW went through to pipe clean drinking water to people’s homes and businesses?

Monster Soup and the Grand Junction Nuisance

A popular postcard from the 1820s shows Monster Soup commonly called Thames Water. Here the microbes in the water, the ones that caused Cholera, Thyphoid and others are depicted as the ancient monsters on sea faring maps.

In 1827, a disgruntled customer wrote and printed a pamphlet for the masses and The Dolphin or the Grand Junction Nuisance. The author sent a sample of the GJWW’s water for analysis and had included the replies. Dr. William Lambe comments on his analysis were:

“ … and observed the great impurity of the specimen of water shown to me, I cannot doubt, that this water is loaded with noxious matter; much of which is obvious to the eye and much, no doubt, is contained in solution.”

The pamphlet was a best seller and water quality was being debated in parliament. There was a select committee hearing and the transcripts of the evidence presented are in the Museum’s archives.

The water works was then based at Chelsea, and so one of the doctors from the Royal Chelsea Hospital was called to give evidence. When asked if the state of the water was causing his patients to be ill, he answered that he wouldn’t know as they mostly drank beer.

With the evidence mounting, pressure was brought to bear on the GJWW.

From the slightly angry tone of the GLWW Chair of Trustees’ letters to then Prime Minister, Robert Peel, the GJWW weren’t too pleased that they weren’t invited to give evidence themselves or being told what they needed to do. Although it might have been his gout which was causing him the most distress!

A small experiment moves to a Grand scale

At the same time, James Simpson was working for GJWW and had set up a small experiment in an acre of grounds there at Chelsea. He’d taken an idea from his travels to waterworks around the UK, especially from Glasgow, and created an experimental water filter.

In this experiment he created a small basin within the ground using different layers of fine and coarse sand and gravel to filter the water. The experiments were a success – not only was the larger debris removed so that the water looked clean, but it also had the added benefits of starting to remove the bacteria that would make people ill.

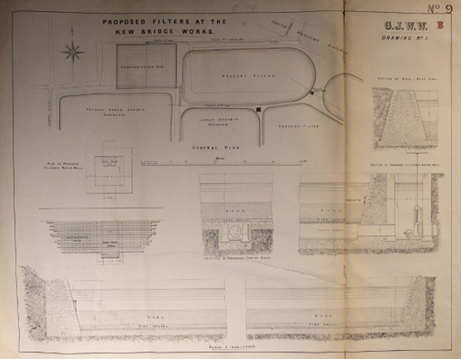

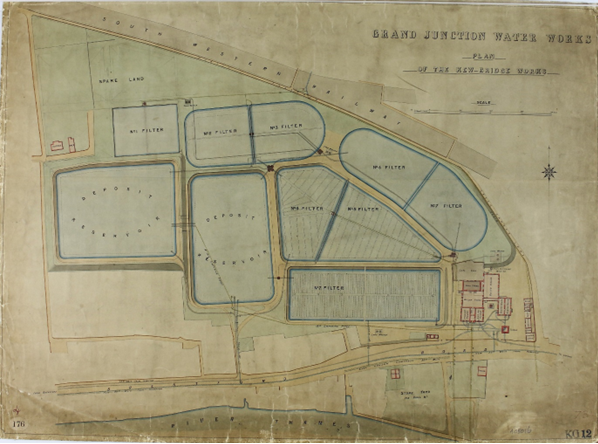

Plans to build a new water pumping station at Kew Bridge, utilising larger scale filter beds, began to be made.

In 1838 the new Kew Bridge Pumping Station was complete with 2 reservoirs and 7 interconnected filter beds.

The sand had to regularly cleaned, so this was a regular sight at Kew Bridge, when water stopped being fed into the top of the filter beds.

Today the filter beds have been replaced by tower blocks, with the remaining section now the Museum’s garden.

The lasting legacy of Georgian and Victorian engineering.

James Simpson’s improved filtered and clean water supply combined with Joseph Bazalgette’s sewer improvements 30 years later saved millions of lives in London.